Editor’s Note: This is the first in a two-part series looking at the issue of building unity at SHC when — according to national reports — unity seems so difficult to achieve nationally. Part one of the series looks at the nation’s political divide.

At Spring Hill College, the political divide is apparent to some, yet nonexistent to others. In order to combat political polarization, the college has created a platform that allows students to discuss current socio-political issues. Student culture at the college, however, disguises the political division that has captured the rest of the nation.

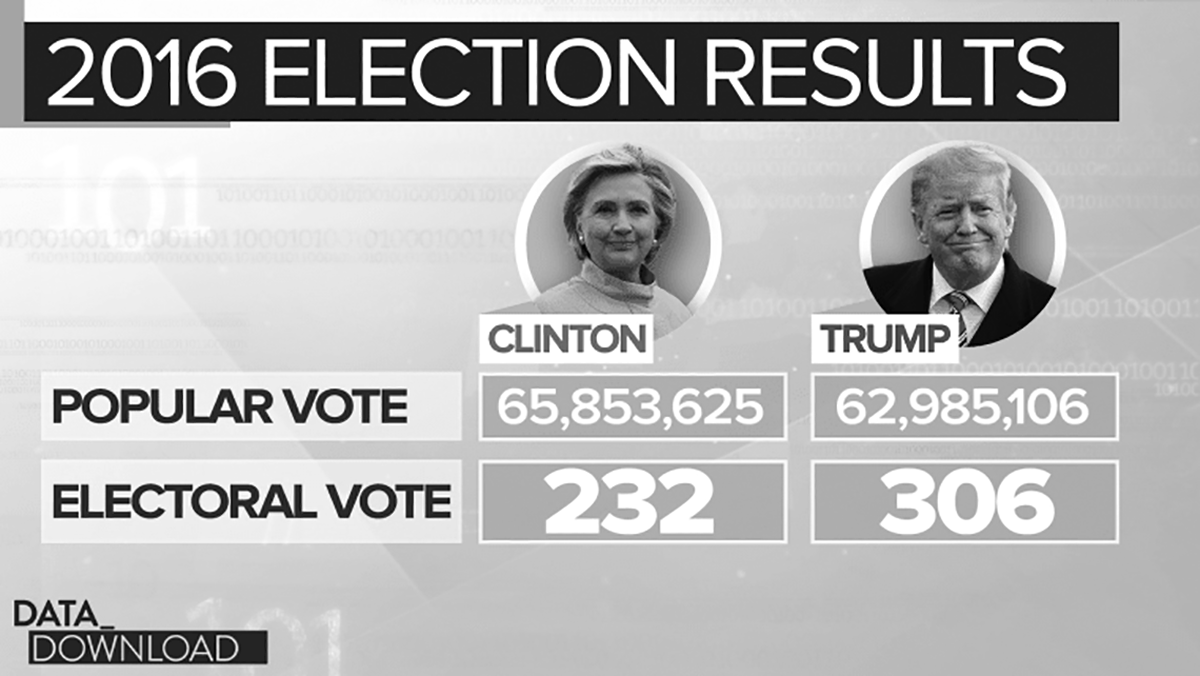

After the 2016 presidential election, a divide grew on campus that left many wondering how college students would close the division. One year later, multiple groups continue to have differing opinions on how wide the chasm is after the college’s efforts to close it. Tom Hoffman, a political science professor at SHC, says, “We are coming close to the level of division in our country as it was in the 19th century.”

The greatest polarization in America due to ideologies and beliefs came during the Civil War. The Confederacy battled the Union over beliefs about slavery and states’ rights. Hoffman suggests that each party, having “refined their ideologies,” caused the partisan polarization, which in turn led to many national social issues. According to a 2014 poll by the Pew Research Center, “The ‘median,’ or typical, Republican is now more conservative than 94 percent of Democrats…And the median Democrat is more liberal than 92 percent of Republicans.” As a result, the percentage of mixed ideologies has decreased from 49 percent in 1994 to 39 percent in 2014.

In regards to Spring Hill, the division is not as visible. The Jesuit ideology that permeates through SHC caused the institution to be seen as “a very non-conservative institution.” Hoffman goes on to mention that “Jesuits have a kind of reputation of being on the left.” This ideology, according to Hoffman, shapes the majority of SHC’s culture due to the “lack of a range of social background.” This background on campus is that of students who, to a large majority, agree with the ideals and values that are supported by the left.

In today’s social revolution, people often surround themselves with news, ideas, images and people that believe in the same things that they do. This causes what Hoffman calls an “echo-chamber.” Jennifer Frederick, an SHC senior and president of the Progressive Club, describes herself as “fairly liberal.” She believes SHC has its divisions, but students are “usually more open-minded.” She attributes this open-mindedness to the faculty of SHC, “[who encourage] us to understand why we believe what we believe.” Further, she attributes it to the Jesuits, whose social justice ideals encourage students to understand surrounding issues.

Junior international business and computer information systems major, Annabel Yates, agrees that many SHC students simply follow the beliefs of others around them. Yates explains that her beliefs are more conservative in nature. She says, “I’ve been raised that way, but I have taken classes and have learned things through school that have helped me agree with it.”

For Yates, the division of political parties on Spring Hill’s campus has become obvious. She explains that this is a result of the faculty expressing their own ideologies into the classroom. One of her worries is that those with mixed ideologies do not speak up for fear of being associated with the extremes. She encourages students to research both parties by exposing themselves to multiple media outlets with opposing viewpoints.

Through social media, the United States has fallen into the cycle of echo chambers. Surrounding oneself with news and people that share one’s own ideology, alienates one, or an entire society, from dialogue with opposing viewpoints. NPR.org considers this activity a “filter bubble” for the reason that it allows people to choose what they see and don’t see.

In early 2014, the Pew Research Center released another survey to document the relationship between political polarization and media habits. As to consistent conservatives, the Center found that 47 percent use Fox News as their main source of political news, making them the most “tightly clustered around a single news source.” Further, they distrust 24 of the 36 news sources measured in the survey, yet 88 percent fully trust Fox News. Among consistent liberals, the Center found that they rely on a greater range of news sources (like NPR and the New York Times) than others, with NPR, PBS and the BBC being their most trusted news sources. Further, they “are more likely than those in other ideological groups to block or ‘defriend’ someone on a social network–as well as to end a personal friendship–because of politics.”

Father Michael Williams S.J. believes that the inability to have “dialogue between two opposing ideologies leads to the polarization” of society. The Jesuits have not stayed an objective order, and have faced criticism for their ideologies and political siding. When asked what the Jesuits teach to combat political polarization, Williams responded, “Pope Francis and the Jesuits teach theology of encounter.” It is this teaching, recommended by the pope, that brought about changes in SHC’s social culture.

Frederick and Yates have seen discrimination from both sides of the political spectrum on the college’s campus. Frederick described the atmosphere on campus, post-presidential election: “You could see right after the election that our campus was divided…I remember people shouting outside ‘Build that wall!’ at 2 a.m. the night after the election.” For her, SHC is a welcoming place, but the election made her realize it’s not a bubble.

Yates spoke about seeing Trump stickers scratched off and vehicular damage. “I have seen what the student body does when you actually preach what you believe in,” Yates said dejectedly.

Following the election of Donald Trump as the 45th president of the United States, SHC instituted the idea of community conversations or “Who’s my Neighbor?” talks. These discussions were started by a group of students, faculty and staff members in hopes of facilitating constructive dialogue about social and political topics. The hope was to avoid conflicts outside the classroom and in society.

The theology of encounter deals with learning from experiencing and analyzing. Students agree that these dialogues are a positive addition to the school’s political standing. Frederick believes the talks have helped people with opposing views to reach a middle ground. However, she states, “We need to recognize that not everything is up for debate. You don’t get to advocate for Nazism.”

Like Frederick, SHC sophomore and Libertarian Michaela McLeod agreed that the “Who’s My Neighbor?” talks have helped unite the campus. She described why they were important: “Having those guided conversations keeps people from just yelling at one another.” Through the community conversations and classroom sessions dealing with inclusion and dialogue, Spring Hill College combats polarizing behavior and helps bridge the gap between ideologies, something that has yet to be done on the national level.